One decision changed Eurovision forever: how five European countries guarantee a final spot every year-and the economic crisis that nearly wiped out the contest. And how did Dana International affected this move?

In a contest where we debate song quality annually, some have long secured guaranteed entry to the final-regardless of their song’s merit. The Big 5 have become synonymous with privilege in Eurovision, but few understand how this decision was born and what led to it. Germany, the United Kingdom, France, Spain, and Italy enjoy permanent final spots, no matter the quality of their entries.

How did they become untouchable? Was it a default choice or a power move to save the contest? And what happened in 1996 when Germany nearly pushed Eurovision to the brink of collapse? This article dives deep into the story everyone has heard but few truly grasp.

The Song That Nearly Bankrupted Eurovision

Eurovision 1996 caused significant upheaval within the European Broadcasting Union (EBU). That year, participation was approved for no fewer than 30 countries, prompting a preliminary elimination round judged by participating countries’ juries. This pre-qualification round was not broadcast, but ultimately seven of the 29 competing songs were eliminated, as Norway, the host country, automatically qualified for the final. The seven eliminated countries were Hungary, Russia, Denmark, Romania, North Macedonia, Germany, and Israel – represented by singer Galit Bell with the song “Shalom Olam“.

Germany sent singer Leon with the song “Blauer Planet” (“Blue Planet”). The song placed 24th in the pre-qualification with 24 points, disqualifying Germany from the contest, as only 22 countries, plus host Norway could participate in 1996’s edition. Germany’s failure resonated all over Europe – without Germany, a major financial pillar for the contest, Eurovision nearly collapsed. The contest, scheduled to take place in Oslo, Norway, was almost canceled. Watch the German song for Eurovision 1996:

How the Big 5 Concept Was Created and Its Impact on Eurovision 1996

Originally called the Big 4, the group included Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Spain. Italy joined in 2011, becoming the fifth member.

Originally called the Big 4, the group included Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Spain. Italy joined in 2011, becoming the fifth member.

Since Eurovision is a non-profit institution, all participating broadcasters are public entities funded by the host country’s broadcaster, sponsors, and participation fees from all broadcasters. These fees are based on solidarity principles-wealthier countries pay higher fees, calculated by population, number of active broadcasters in the EBU, socio-economic status, and more.

In 1996, Germany’s elimination meant it was exempt from paying annual participation fees. Germany, with its strong economy and large EBU membership via the massive ARD network, was a crucial financial contributor. Its absence caused a severe financial blow, nearly canceling the Oslo contest.

How Was Eurovision Saved from Financial Collapse?

To rescue Eurovision from financial collapse, it was decided that the four countries paying the highest participation fees would be exempt from elimination from the contest, even if they achieved low results. These four countries are Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Spain. Ahead of Eurovision 2004, when the semi-final stage was introduced for the first time, it was decided that these four countries would not compete in the semi-final and would advance directly to the final.

To rescue Eurovision from financial collapse, it was decided that the four countries paying the highest participation fees would be exempt from elimination from the contest, even if they achieved low results. These four countries are Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Spain. Ahead of Eurovision 2004, when the semi-final stage was introduced for the first time, it was decided that these four countries would not compete in the semi-final and would advance directly to the final.

Ahead of Eurovision 2011, after much effort and persuasion, the European Broadcasting Union succeeded in bringing Italy back to the contest, after its absence from 1998 to 2010. Italy also pays a heavy participation fee due to its large population, so to facilitate its return and because of the annual fee it must pay, it was decided to grant Italy an additional guaranteed spot in the final alongside the four major contributors.

Sponsored Songs That Avoided Elimination Despite the System

After Eurovision 1996, it was decided to change the elimination system because the existing method had caused a major financial collapse. For Eurovision 1997, a new elimination system was introduced. This new system took the entire list of participating countries and calculated an average score based on the last five participations (except for 1997, where the average was based on the last four participations). Absences were not counted, and the countries with the lowest averages were eliminated from the competition for the following year but were guaranteed an automatic spot the year after that.

A country that decided to withdraw despite having an average above the threshold would free up a spot for the next country on the list. The four sponsoring countries at the time – Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Spain – were included in this system and later were even saved from elimination if their average was too low to qualify. It is possible that if they had not been part of the Big 4, many absences would have been recorded throughout the competition.

The Average Score System: How Were Countries Affected?

Ahead of Eurovision 1997, there were no unusual cases among the major contributors, as according to the average score calculation, the United Kingdom ranked third, France sixth, Spain 15th, and Germany 17th. Italy, due to many absences, was placed 20th.

Israel, whose average ranked 23rd, decided to withdraw from the contest because it was scheduled on Holocaust’s Mmeorial Day, thus vacating its spot for Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Ahead of Eurovision 1998, according to the average score calculation, the United Kingdom rose to second place due to its 1997 win. France moved up to fourth place, Spain to tenth, and Germany dropped to 21st. According to the protocol, Germany was supposed to be absent from the contest, but Italy’s withdrawal freed a spot for Germany. In Eurovision 1998, the major contributors showed slight signs of weakening: France, represented by Marie Line, finished 23rd with only 4 points – a result that could have jeopardized France’s participation in Eurovision 1999 if it had not been part of the Big 4.

How Did Dana International Influence the Big 4?

Ahead of Eurovision 1999, the United Kingdom dropped in ranking due to Israel’s victory the previous year with Dana International and her song “Diva”, returning to third place. Germany began gaining momentum, climbing to tenth place, while France’s low result dropped it to 13th, and Spain returned to 15th position. In Eurovision 1999, the Big 4 showed more severe signs of decline – France finished 19th with 14 points, and Spain ended last with only one point. Following this double setback, it was decided that these four countries would be guaranteed a spot in the contest even if their results would otherwise lead to elimination.

Ahead of Eurovision 1999, the United Kingdom dropped in ranking due to Israel’s victory the previous year with Dana International and her song “Diva”, returning to third place. Germany began gaining momentum, climbing to tenth place, while France’s low result dropped it to 13th, and Spain returned to 15th position. In Eurovision 1999, the Big 4 showed more severe signs of decline – France finished 19th with 14 points, and Spain ended last with only one point. Following this double setback, it was decided that these four countries would be guaranteed a spot in the contest even if their results would otherwise lead to elimination.

Germany, however, continued to shine. After placing seventh in 1998, Germany finished third in 1999 with the German-Turkish band Surpriz and their song “Reise Nach Jerusalem” (in English: “The Journey to Jerusalem”), which was sung in German, Turkish, and English. The band chose to sing the last line in Hebrew – “Shalom, shalom, narim itchem yadayim, shalom al ha’olam mi’Yerushalayim” (“Peace, peace, we raise our hands with you, peace upon the world from Jerusalem”) – which endeared them to Israeli audiences, who awarded Germany 12 points.

Ahead of Eurovision 2000, the United Kingdom rose to first place. Germany, despite its strong results, dropped to 11th place, Since their 1994 result was removed from the calculation. Despite finishing last in 1999, Spain remained in 15th place. France continued to decline to 19th place, which according to the protocol meant France was supposed to be absent from the contest.

A notable event in the scoreboard was the deduction of one-third of the points Croatia received at Eurovision 1999, due to “human voices” in the song’s backing track, which violated the contest rules. At Eurovision 2000, France, represented by Sofia Mestari, finished in 23rd place with only 5 points, a particularly worrying trend for France, which had delivered very low results for three consecutive years.

Return to the Placement System: Which Country Cried Like a Baby?

Ahead of Eurovision 2001, the average score system was used for the last time. After that, it was decided to return to the old elimination system used between 1993 and 1995 – elimination based on placement in the current contest. In other words, for Eurovision 2001, it was decided that countries finishing 16th or lower would be eliminated from Eurovision 2002.

Ahead of Eurovision 2001, the average score system was used for the last time. After that, it was decided to return to the old elimination system used between 1993 and 1995 – elimination based on placement in the current contest. In other words, for Eurovision 2001, it was decided that countries finishing 16th or lower would be eliminated from Eurovision 2002.

In Eurovision 2001, Latvia, which participated for the first time in Eurovision 2000 and finished third, pushed the United Kingdom down to second place. Germany rose to eighth place after three strong results, while Spain continued to decline and recorded another low result in 2000, dropping it to 22nd place in the table. France, with its third consecutive low result, continued to fall to 25th place. According to protocol, Spain and France were supposed to be absent from the contest. However, in Eurovision 2001, France broke the negative streak when Natasha St-Pier reached fourth place – bringing France back to Eurovision 2002 with high confidence.

Eurovision 2002 faced a shortage of contestants after elimination. 22 countries appeared on the participant list, composed of the top 15 places from Eurovision 2001 and seven countries eliminated due to low averages after Eurovision 2000 who were due to return. As a result, Israel and Portugal (16th and 17th places in Eurovision 2001) were offered to participate and complete the list to 24 countries. Israel accepted and sent Sarit Hadad with the song “Nadlik Beyachad Ner” (in English: “Light a Candle”), which finished in 12th place.

Portugal declined and gave its place to 18th place, Latvia, which confirmed its participation and eventually won against all predictions favoring Malta. The United Kingdom and France shone – the United Kingdom finished third together with Estonia (with 111 points each). France finished fifth, but Germany ended its streak of successes from 1998 to 2001 by finishing 21st.

In Eurovision 2003, one major contributor reached its lowest point: the United Kingdom. The British representatives were the band Gemini with the song “Cry Cry Baby”. The British indeed “cried like babies” after the contest, as for the first time in Eurovision history, the United Kingdom finished last – and to add insult to injury – they ended the contest with zero points! Since then, the United Kingdom has continued to lose its great success year after year, repeatedly finishing near the bottom of the scoreboard and hitting last place also in 2008, 2010, 2019, and again scoring zero points in 2021 – on both Jury and Televoting segments. Exceptions were their results in 2009 and 2022.

Single Semi-Final System: Which Countries Earned a Final Spot Thanks to the Big 4?

Ahead of Eurovision 2004, it was decided to introduce a new elimination system – splitting Eurovision into two broadcasts: a semi-final and a grand final. According to this system, the big 4 did not participate in the semi-final and advanced directly to the grand final, along with the top ten countries from the previous year. These 14 countries were joined by ten qualifiers from the semi-final, making the final consist of 24 countries. However, this system had a slight loophole-what happens when one of the major contributors finishes in the top ten? Places 11th–14th from the previous year, depending on how many major contributors finished in the top ten, were guaranteed a spot in the final. This happened frequently over the years.

-

In Eurovision 2003, Spain finished 8th, so Ireland, which finished 11th, qualified for the Eurovision 2004’s grand final.

-

In Eurovision 2004, Germany finished 8th and Spain 10th, so Russia and Malta, which finished 11th and 12th respectively, advanced to the Eurovision 2005’s grand final.

-

In Eurovision 2005, all four major contributors finished in the bottom four places, but the withdrawal of Serbia and Montenegro, which finished 7th, opened a spot for Croatia, which finished 11th, to qualify for the Eurovision 2006’s grand final.

-

In Eurovision 2006, no major contributor finished in the top ten, so no additional country secured a guaranteed spot in the Eurovision 2007’s grand final.

Two Semi-Finals System: Do the Big 5 Truly Justify Their Direct Spot in the Final?

Eurovision 2007 marked a turning point in the contest, featuring the largest semi-final in its history with 28 countries competing. Following this, it was decided to split the semi-final into two separate shows, reducing the maximum number of participants in each semi-final to 19.

The Big Five countries – Germany, France, Italy, Spain, and the United Kingdom – continue to guarantee themselves a direct spot in the grand final. But is this privilege truly justified? The results do not fully reflect agreement from either the judges or the audience with this rule. Which songs would not have passed the semi-final stage if they had to compete in it? It turns out quite a few.

- In Eurovision 2008, none of the Big Five achieved impressive results – Spain performed best, finishing 16th; France placed 19th; Germany and the United Kingdom tied with Poland, all three closing the scoreboard with 14 points each.

- Eurovision 2009 was somewhat kinder to the UK and France, who finished fifth and eighth respectively, but raised doubts about Germany, which finished 20th, and Spain, which came 24th, with only Finland behind it.

- Eurovision 2010 was one of the most extreme years for the Big Five. Germany won, while the United Kingdom finished last. During Spain’s performance, activist Jimmy Jump (Jaume Marquet i Cot) invaded the stage. Spain performed again and finished 15th.

- Ahead of Eurovision 2011, Italy returned to the Big Five, securing second place in Düsseldorf. The host, Germany’ finished 10th, the United Kingdom 11th, France 15th, and Spain 23rd.

For the First Time – 26 Countries in the Final

Eurovision 2012 was the first contest since 2003 to feature 26 countries in the final. For two countries – this time the United Kingdom and France – luck was not on their side. Despite favorable coverage of the French entry, Anggun finished 22nd. The United Kingdom finished 25th, with only Norway behind them. In contrast, Germany, Italy, and Spain achieved strong results, consecutively taking 8th, 9th, and 10th places respectively.

In Eurovision 2013, the running order draw was changed, and the Big Five showed even more signs of decline, with low results accumulating over the years. In 2013, four Big Five countries and the host finished at the bottom of the scoreboard: The host, Sweden, finished 14th, the United Kingdom 19th, Germany 21st, France 23rd, and Spain 25th – only Ireland finished below Spain. Italy was the only Big Five country to place in the top half, finishing 7th.

Eurovision 2014 continued the trend of decline among the Big Five. For a whole decade afterward, there was always a Big Five country or host finishing last, sometimes not alone. It appeared the Big Five were showing signs of breaking – or perhaps complacency – suggesting that if they were in the final but not interested in winning, they might intentionally send a weak song to avoid hosting. In 2014, France finished last, Italy 21st, Germany 18th, and the United Kingdom, which was highly favored in betting odds, only reached 17th place.

Eurovision 2015 was particularly unusual, as it was the first time since 1958 that the host country finished last. Moreover, it was the first Eurovision where the host, Austria, scored zero points at home, sharing this embarrassing result with Germany. The United Kingdom and France finished 24th and 25th respectively, and Spain placed 21st. Italy was the only Big Five country to stand out, finishing third.

In 2016, Germany continued occupying the last place slot, the United Kingdom placed 24th, Spain 22nd and Italy 16th. France was the only Big Five country to perform well, finishing sixth.

Chronic Bad Luck?

From Eurovision 2017, the bad luck of the Big Five returned strongly, also affecting the host countries. In 2017, the three countries closing the scoreboard in ascending order were the Big Five members Spain and Germany, along with the host Ukraine, which finished 24th.

From Eurovision 2017, the bad luck of the Big Five returned strongly, also affecting the host countries. In 2017, the three countries closing the scoreboard in ascending order were the Big Five members Spain and Germany, along with the host Ukraine, which finished 24th.

Eurovision 2018 shook the host Portugal from victory straight to last place, with the United Kingdom finishing 24th and Spain 23rd. In contrast, Germany and Italy performed very well, finishing fourth and fifth respectively. The blow did not skip Israel, which hosted Eurovision 2019 and finished 23rd, with Spain in 22nd place, Germany 25th, and the United Kingdom last. Italy finished second, just 26 points behind the winner, the Netherlands.

And What About Recent Years?

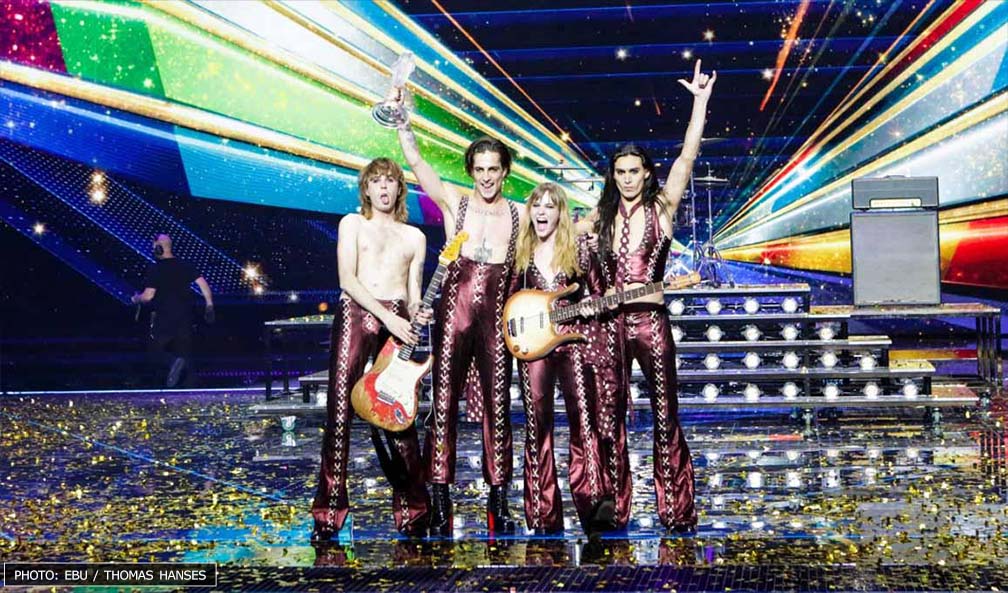

Eurovision 2021 was the most extreme in results for the Big Five – with two countries finishing first and four finishing last. Italy won, France came in second. In contrast, the United Kingdom finished last with zero points, Germany was 25th, Spain 24th, and the host Netherlands finished 23rd.

Eurovision 2021 was the most extreme in results for the Big Five – with two countries finishing first and four finishing last. Italy won, France came in second. In contrast, the United Kingdom finished last with zero points, Germany was 25th, Spain 24th, and the host Netherlands finished 23rd.

Eurovision 2022 also showed extremes, with the United Kingdom and Spain finishing second and third. The host, Italy, finished sixth, while France and Germany closed the final scoreboard in 24th and 25th places, respectively.

Eurovision 2023 was no exception, with Germany finishing last for the second consecutive year and the host United Kingdom placing 25th.

Eurovision 2024 showed a somewhat fresh start for the Big Five, as none of them finished last. Some even managed to recover relatively well, except Spain, which finished 22nd. Will Eurovision 2025 bring the Big Five back into the spotlight and improve their tarnished reputation?

What About the Future?

There is no doubt that the Big 5 are an integral part of Eurovision’s DNA, but in recent years something has started to creak. More and more viewers openly question whether this privilege harms the character of the competition and public trust in it. Meanwhile, musical achievements continue to be disappointing in many cases, raising the question of whether it is time to rethink the model.

As the years go by and the audience becomes more critical, the question arises: is this model still relevant? Perhaps a fundamental change will be required in the near future – one that will cancel the immunity of the powerful countries and return the contest to a state where every country is measured by the same standard. Until then, the Big 5 will continue to sit at the head of the table – for better or worse.